HIS national sprint records stood for decades and he was once the “Fastest Man in Asia”.

But at 76, Tan Sri Dr M. Jegathesan has now eased on the throttle with his priorities in life changed.

Jega, as he is more fondly known, is held in high esteem.

Many have been intrigued by how he could combine his track prowess and academic excellence in the 60s to become one of the most distinguished personalities in the country.

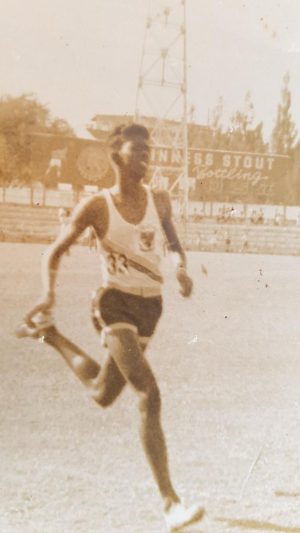

For eight years from 1960, Jega was virtually unbeatable and unstoppable in the sprints.

His National 100m record of 10.38 secs and 200m record of 20.92 secs had at one point also seemed unbreakable, not until they had stood for about 30 years and 49 years respectively.

Besides the sprints, he was also a powerful 400m runner with a personal best of 46.3 secs in the 1966 Singapore National Championships, which also stood as a Malaysian national record for decades.

Jega was in Penang recently for the Universiti Sains Malaysia convocation in which former squash queen Datuk Nicol Ann David was bestowed an honorary doctorate in Sports Science by USM chancellor Raja of Perlis Tuanku Syed Sirajuddin Syed Putra Jamalullail.

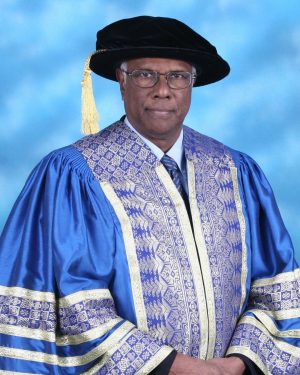

“Nicol is the first recipient of the award and she fully deserves it. She has earned the recognition through her own sporting success as well as being a virtuous person,” said Jega, who was appointed USM pro-chancellor in 2011.

Although the USM pro-chancellorship is an honorific title, never before had a Malaysian of Indian descent been accorded that stature.

And this came on the heels of him being honoured with the “Tan Sri” title by the Yang diPertuan Agong Sultan Mizan Zainal Abidin on June 5, 2010 for his meritorious service.

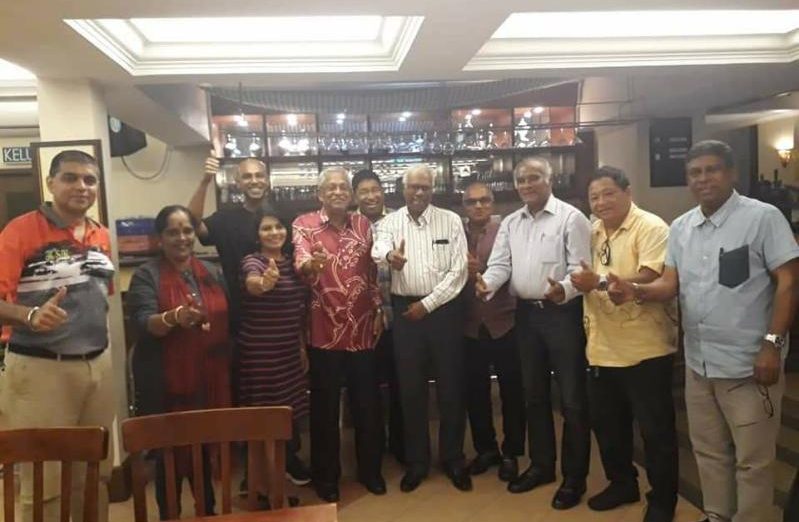

During his trip to Penang, Jega also caught up with some friends, one of whom was Podim Hatia. The secretary of the Penang Masters Athletics Association and his wife Ruth Mary, hosted Jega and a few other friends to a dinner at the Penang Sports Club.

When you have the privilege of meeting a sports legend, the topic was invariably about sports – the past, present and future.

His past was filled with many achievements. He represented Malaysia at three Olympic Games – as a 16-year-old Form Six student at the 1960 Rome Olympics, a medical student at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics and a qualified doctor at the 1968 Mexico Olympics.

It was at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics that he clocked 20.9 seconds for the 200 metres at the semi-final, a rare distinction for a Malaysian.

He repeated that feat in the Mexico Olympics four years later. Jega also competed in two Asian Games. He became the first Malaysian to win a gold medal in the Asian Games in Jakarta in 1962, winning the 200m, and captured three golds – 100m, 200m and 4x100m – in the 1966 Bangkok Asian Games.

The treble success in Bangkok earned him the nicknames “Flying Doctor” and “The Fastest Man in Asia”.

The Games also arrived just two months before his final MBBS (Bachelor of Medicine) examination which earned him his Dr title.

What made it more memorable was that he received personal congratulatory messages from the then Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman and Deputy Prime Minister Tun Abdul Razak.

He was also named the nation’s first Sportsman of the Year in 1966.

Jega still vividly remembers his first Olympics in Rome in 1960.

He was eliminated in the first-round heat of the 400m while India’s Milkha Singh, known as “Flying Sikh”, narrowly missed out on the bronze by finishing a creditable fourth place in the final.

“So, when Milkha came to the Jakarta Asian Games in 1962, everyone was expecting him to win the 200m and 400m. He did know me because in those days, there was no Google.

“To me, his best years were in 1960 and 1961. After that, he started to fade. He did not take me seriously when someone told him that I could provide him a stiff challenge in the 200m. I kept very quiet and when the race came, he finished fourth – not only beaten by me but two others as well.

“After that, Milkha retired. Still, he was my idol, once Asia’s best 400m runner and he could give the Americans a run for their money.”

There was another riveting race that Jega could not forget.

Invited to give a talk at the National University of Singapore, his alma mater, some years ago, he recounted how he won the 100m gold medal in the 1966 Asian Games in Bangkok by beating his Singapore arch rival, C. Kunalan, and Japanese Hideo Iijima in a photo finish.

“I wanted to win the gold medal and graduate as a doctor in a short span of time in 1966. I knew Kunalan would be there.

“So, I used all the tricks of mental preparation. Every night, I prepared myself mentally. Every night, I went to sleep and imagined myself winning the 100m race. Every night for two months, in my mind’s eye, I practised the dip.

“This is the power of visualisation and auto suggestion. So, on that day, I didn’t have to think. The dip just came automatically.”

After some tense moments, Jega was adjudged the winner, beating Kunalan by 0.01 second as his torso was nearest to the line. Iijima was placed third.

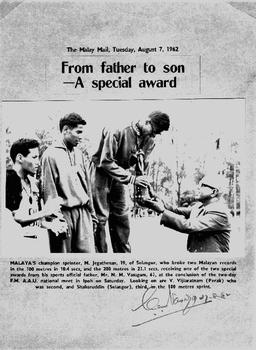

Athletics seemed to run in the blood.

Jega’s father, N.M. Vasagam, a government servant, was the first non-European to win the 440-yard race in the 1920s when the event was opened to non-whites.

He later became the first secretary of the Federation of Malayan Amateur Athletic Union (FMAAU) and the Olympic Council of Malaya in 1955.

All his four sons excelled as an athlete or sports administrator. The eldest boy, Veerasingam, became the secretary of Brunei Amateur Athletic Association, the second eldest, Balakrishnan, took part in the 1954 Asian Games while the third, Harichandra, was a 880-yard champion competing in the 1956 Olympics.

Born in Kuala Kangsar, Perak, Jega received his early education at Batu Road School and thereafter at Victoria Institution (both in Kuala Lumpur).

But at the age of 12, his father sent him to Singapore to study at the Anglo Chinese School (ACS) under the care of his sister and brother in law. And it was during the formative years there that Jega’s raw athletic talents were polished by different school teachers and coaches such as Tan Soo Liat , Maurice Nicholas and Tan Eng Yoon of Singapore and expatriate American coaches as Thomas Rosandich, Bill Miller and Stan Wright.

He then proceeded to study medicine at the University of Singapore and graduated in 1967.

Asked how he could cope with so much relentless training on the track as well as without skipping a year in his medical studies, Jega said the main thing was for the person to determine what his or her priorities in life are.

“If you have decided that while you are going to focus on sports and you also don’t want to miss out academically, then the biggest secret is that you got to learn this whole thing called time management.

“You have to learn how to allocate the time around your life in such a manner that you are able to do the necessary things to achieve what is required from both these fields.

“But this doesn’t come easily. It comes at the sacrifice of some other things, like having fun with your friends, going to parties. Which your friends may or may not understand. So, that is something you got to face up to.

“It’s a personal decision that you make and then you got to make the decision work by being, most importantly, disciplined. If you are not disciplined, then it is very difficult.”

Sadly, there are not many school children nowadays pursuing sports excellence, especially in track and field.

Jega said the dynamics in schools have changed. Those days, he said schools were a spawning ground of sports persons and they had very dedicated sports masters well trained in physical education. Furthermore, even some schools don’t have sports fields anymore while others emphasise on academic pursuit.

“Nowadays, for instance, a lot of young children are taken up with digital entertainment. Unlike our time, we looked forward to running to a field, either play a game of hockey or football or run around, jump or whatever it is.

“But today, young people would rather sit in front of a laptop and play computer games. That is why in a way you find esports becoming more and more popular among various sports organisations. They try to cater to the interest of the youth.

“E-sports is big money. While it is serving the current purpose, it is not a substitute for physical activity out in the open. Not just only for sporting pursuit but also physical health and keeping a fit body.”

Jega quit athletics when he was at the top, retiring after the 1968 Mexico Olympics. He then focused on his profession as a doctor, serving the government health service for 32 years, including the posts of Director of the Institute for Medical Research (IMR) and Deputy Director-General of the Health Ministry.

His achievements and awards are too many to list. He was once the deputy president of the Olympic Council of Malaysia (OCM), the deputy chef de mission for the 1966 Atlanta Olympics and the chef de mission for the 2004 Athens Olympics for the Malaysian contingent.

Jega also sat on numerous medical commissions, and until recently had been the chairman of both the medical commission of both the Olympic Council of Asia and the Commonwealth Games Federation.

“As of this year, with my completion of my four-year term and I have done a few cycles of this, I have decided to step down from these positions.

“I think it’s time other people are also given the opportunity to be able to do these tasks. I will, however, be still involved as an adviser or supporter in different ways.

“All the time in my life, I had earned my living through being a doctor and working in the medical sector, both initially in full-time government services and then in the private sector.

“But all my contributions in sports have been entirely and always been on a voluntary basis – either as an elected official or a volunteer, never in a paid position. So, I run these two parallel. Now I am at a stage where I have retired from both sides officially.”

Speaking of anti-doping, Jega said the use performance-enhancing drugs is an acknowledged evil in the sports scene today.

That is why he said the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) and the national anti-doping agency have been working to first educate the athletes not to be involved in drugs and at the same time create deterrent measures by conducting tests.

While admitting that they cannot completely eradicate the drug menace, Jega said if they don’t have the deterrent measures in place, it would be a free for all.

Malaysia is still chasing for the elusive Olympic gold medal and Jega feels that the prospects for the national team are technically in badminton, diving and archery.

Jega said high jumper Lee Hup Wei, who recently reached the final of the high jump in the World Athletics Championships in Doha, could be one to watch if he qualifies for the Tokyo Olympics.

Hup Wei, a 32-year-old wild card entry in Doha, soared to a personal best of 2.29m. He has to clear 2.33m to qualify for the Tokyo Olympics.

Jega now spends more time with his wife from Seremban, Tan Lee Hong, whom he married in 1969, their three children and six grandchildren.

Both were also studying at the University of Singapore but the chemistry between them took place when Jega was posted to the General Hospital Kuala Lumpur (GHKL) and Tan was working as a pharmacist in a company across the road from the hospital.

All their children – Ashe-Lee and husband Peter Jones, Shirene Jegathesan, and Nick and wife Lisa Crowfoot – are living in Melbourne, having studied and obtained their qualifications and getting married there. Ashe-Lee, a lawyer by training, is currently the COO of a public listed company whilst son Nick is an anaesthetist in the private sector. Their eldest grandchild, Briana Jones, 19, was previously an Australian champion in the doubles for kayak under-18. The other grandchildren are Nathan Jones, Caelan and Ewen Jegathesan-Lamb, Laura and Alex Jegathesan.

Occasionally, Jega is invited to give talks on motivation or medicine. He would often tell his audience to learn to prioritise and never be afraid to dream.

“While you aim for the stars, have your feet planted on the ground because you must always be in touch with reality. But never be afraid to dream; because of our dreams, come visions. Visualise your plan and make it happen.”

Story by K.H. Ong